“Jus pikkid up buddy, jus pikkid up. Thaet 60 lac BMW na, maine toh by Gaud last week hi buy ki. You should aulso pikkid up buddy.”

Such is the idea of excess in Punjabi culture, that even the ordinary roti goes with a rhyming vocabulary accompaniment. While the rest of India – particularly their more mathematically formidable Tamil counterparts – looks on in amused bewilderment, Punjabi culture proudly crested on the honed biceps of Punjabi men carries on blissfully; wearing, drinking, eating, thinking, abusing, driving, buying, watching, listening, gossiping, doing, reading, expressing, talking and showing in extravagance. Baroque is an incontestable way of life in north India.

What, therefore, must be the idea of refinement for the Punjabi man? Is there one? For surely, he does not consider his cirque de display loud.

Ours is a valiant attempt at putting our hands into the codes and the meanings behind the stuffed lions and the much more lively Punjab da sher.

The Voice of the Land

Mr. Bhushan Sethi is the Former Deputy Home Secretary of Punjab, reads up a lot on economics, is an active investor in real estate and to beat all Punjabi stereotypes, is a teetotaler. His son Vivek, is a Supreme Court lawyer by profession, loves long drives and food and champions education above all else. When we asked them what a refined life – the life that a civilized human being should lead – for a Punjabi is, the one thing they both responded with was the ownership of land and a life sourced from the soil.

For this father son duo of Chandigarh, the idea of land or zameen, is almost a sacred idea. A prevalent idea across Punjabi’s, the seeds of this diehard love for their land lies in Punjab’s history. The northern Indian and Pakistani area now known as Punjab on both sides has been conquered by 16 different empires and races in the last 3000 years. Punjabis over centuries have been displaced constantly and, hence, have had to fight for their homeland.

Related to a Punjabi’s zeal for his land is his idea of space. The idea of sophistication in shelter is not as much about aesthetics as it is about expanse. People want the ‘kothi’ and not the ‘ghar’.

This has resulted in a strong sense of pride and possessiveness about land. They look to make themselves self-sufficient through the land itself. Punjab is one of India’s most agriculturally fertile states. Mr Bhushan Sethi told us that 60% of the Punjabi population is rural and are farmers. In fact, no matter what Punjabis do or where they are in the world, they will proudly call themselves ‘sons of the soil’.

It is this thinking that has instilled in them an idea of not being dependent on anything but the land. Hence, land and the food it produces play a key role in the idea of refinement for a Punjabi.

Punjabis lay special emphasis on their food and they take it with them wherever they go. It is no surprise, therefore, that it is Punjabi cuisine that has made it to all parts of the world more than any other form of Indian food and often passes off as the only kind of Indian food itself.

Vivek told us that Punjab has the lowest level of hunger in India. And eating pure, homegrown and organic food that is high on nutrients is a sign of taste and refinement in Punjab. A lot of Punjabis regard packaged, factory-made and processed food unhealthy. They see it in poor taste and as a sign of an unfortunate, less fulfilling life.

Hence, for Punjabi women, expertise in cooking is seen as an admirable trait, a sign of subtlety and good breeding.

To Punjabis, the respect for food is a sign of appreciation of the finer things in life. That’s why food at Punjabi weddings is a key determinant of the refinement and taste of the hosts. To them, acknowledging the source of the food i.e. the land is a sign of humility and gratitude towards the Almighty.

Hardwork is the Road to Refinement

At 67, Sardar Balbeer Singh, zest for life is what strikes you most. An infectious enthusiasm marked the values and idea of life for this wheat and maize farmer. Balbeer Singh is married and has two children, one of whom works in Kuwait. The other studies at a small college in Jalandhar. Balbeer’s wife makes sure her husband’s effervescence and magnanimous personality stays well-fed through her simple but delicious cooking. Sardar Balbeer Singh loves his buffaloes next only to his wife and children. He looks after his crops as if they spoke to him.

But what keeps the stocky farmer ticking – and indeed a lot of Punjabis – is his passion for his work. Balbeer Singh told us that arguably every Punjabi is in pursuit of only one kind of life – an active, hardworking one. According to him, hardwork is the most revered virtue amongst Punjabis. There is an emphasis on self-sufficiency that makes hardwork imperative. He evocatively puts it as, “Mehnat ki roti khaate hai, muft ki nahi.”

Balbeer thoughtfully told us that such is the willingness to work in Punjabis that, at times, it even overshadows the need for higher education. Hence, in such a culture the choice of livelihood is a key source of refinement. Most Punjabis prefer to have their own farm land and till it or run their own business. These are considered far more respectable than a job. And no matter how educated one’s children are, they will always be expected to continue the family business or profession.

As Balbeer Singh took us on a tour of his earthy hut amidst the farms where he sleeps during the farming season, he profoundly told us that he was brought up on a culture of labour. In fact, most Punjabis are. They are a race proud to be physically laborious. And no one is ashamed to do manual work. A thought-provoking statement followed, “A refined person is humble enough to use his body for physical labour.”

According to Balbeer, refinement is in not assuming arrogance through knowledge or by doing work that involves little physical activity. That is lack of character and a very narrow-minded view on life. It reeks of lack of self-respect and a void of respect for humankind’s potential and for other human beings at large. For a Punjabi, physical health and activity are a key trait of a good life.

In fact, being relentlessly active is not just limited to Punjabis’ view on productivity. Interestingly, it is also how Punjabis view leisure, personal time, familial and social camaraderie and unwinding. According to Balbeer and a few other Punjabis we spoke to, A good Punjabi life is where lots of hardwork is balanced through a life full of openness, expressiveness, active unwinding and camaraderie.

Shyness, they say, is not a Punjabi value. Balbeer jovially told us at the peak of his voice, “Punjabis jo bhi karte hai, dil khol kar aur jee bhar ke karte hai.”

Openness, constant interaction and expressiveness are seen as signs of honesty and good values in Punjab as they reflect a perspective that’s not self-centred and is involving. And for a tightly-knit, small race, unity and camaraderie are essential.

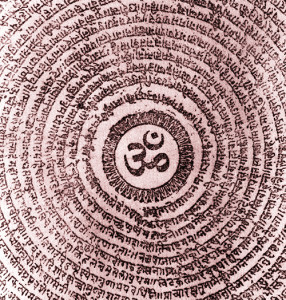

The ideal Punjabi leisure is devoid of pensiveness, sedateness or solitude. It is meaningful when it is meant to be and Sufi music, profound Punjabi folk music, recitals of the Guru Granth Sahib (the holy book of the Sikhs) and discussing philosophy and human existence do form a part of such soulful leisure. But, essentially, being a recluse is not Punjabi and is seen as a sign of unhappiness and unfulfilling living.

Hence, Punjabi folk music can be spiritually and morally inclined but bears the traits of how Punjabis essentially see life. As the day waned and after the buffaloes had been fed, Sardar Balbeer Singh lay down peacefully on his khaat (bed made of simple wood and interwoven jute strings) told us that he prefers to listen to Punjabi folk music of the years gone by as the singers are local and have a sense of purity in their purpose, their lyrics aren’t vulgar, they have goodness and happiness as messages and, hence, he values them over the sizzle and glamour of Bollywood.

Mixing not Gleaning

In the dusty outskirts of Jalandhar, the industrial area is not just home to the livelihood of many Punjabi businessmen, it is also an emblem of the community’s model of progress – inclusive. The competition is intense but its not polarizing.

When we got to 58 year-old Mr NC Goyal’s asbestos products manufacturing plant, his son, Vikas Goel, 31, was rounding up the cash flows for the day. Vikas got married a few years ago and recently became a father. He took his wife to Switzerland for their honeymoon and is an avid reader of Indian authors such as Chetan Bhagat. While his primary focus is his business and the money he makes, he spends a few Sunday evenings writing down his thoughts and sorrows that he hasn’t shared with anyone. But the then throws them away because he asks, “Why dwell on things?”

Vikas and his father shared with us a perspective perhaps unique to Punjabis when it comes to refinement. Like when they do business, Punjabis actually believe in an idea of refinement that is not about gleaning but miscibility. Says Vikas, “We all feel a sense of pride and willingness to be part of the collective. For me, that’s a sign of a refined person.”

It’s not that Punjabis aren’t accepting of individual tastes or behaviour. Everyone is free to do what they want but what the community does detest is the claim of a superior rank based on such taste of behaviour. Mr NC Goyal said with a sense of honesty in his voice, “None of us is as good as all of us.”

Punjabis, the father-son duo said, think of those who see themselves as superior due to difference in tastes as people who are uncivilized, untrained in manners and of poor etiquette and upbringing.

Genuinely belonging to and feeling proud as a part of the community, therefore, is an integral part of a good life for a Punjabi.

Refinement is not about distance or seeking difference. It is about seeking excellence, collaborating and sharing it with everyone. And this is where the Punjabi idea of refinement is different – it is anchored in seeking excellence not just through oneself but through others.

Hence, celebration and sharing are considered key traits of a good life for Punjabis, Vikas told us with elan. The Goyals were unequivocal in telling us that that living life to the fullest is, indeed, inseparable from a Punjabi and is considered a sign of appreciating life and its bounties. Sharing and mixing is also obviously an occasion to display sophistication and taste but that never overshadows the true purpose – a rich community life.

Finding Salvation in the Everyday

Few people are as clear in their head as 37 year-old Harvinder Singh is about the way life should be lived. A father of two young boys, the industrial rubber products manufacturer is a man who prides himself on integrity and doing the right thing. A Royal Enfield enthusiast, a romanticist at heart, a fan of meaningful cinema, Punjabi folk and an SUV lover, Harvinder believes in being there in the thick of things. A spectator, a critic, a well-wisher, an opinion provider – that’s not Harvinder. He’d rather be a helper, the practitioner, a learner who fails but gets up and a good, credible, self-experienced advice giver.

Harvinder’s view on a good life is clear – family-centric, socially involved, religiously committed, fun but not rash, brave and one where the one who takes responsibility is also willing to shoulder the blame.

But perhaps what defines Harvinder is his understanding and practice of bravery and search for salvation or moksha.

Harvinder is tall, well-built. He eats only homemade, organic food. His family has never bought packaged butter or refined cooking oil. They use home-churned white butter and ghee (clarified butter). But Harvinder’s idea of bravery is not inspired purely by the physical. As he says with a wry smile, “Not every Punjabi wants to join the army, prove his masculinity, pick a fight, be loud and aggressive and listen to garish music. In fact, that’s just a handful. But as you know, it takes one rotten fish to spoil the lake.”

Harvinder told us that one has to look beyond perception to get a true idea of Punjabi ideals. He said that it’s an absurd notion to think that an entire race of people is devoid of any meaningfulness in their lives and are like depraved materialists. He laughs it off as arrogance of the pseudo-intellectual. According to him, Punjabis are very meaningful people. Of course, when they want to have fun, they open up. But whatever Punjabis do, they do it to the fullest. Even when its pursuing meaning.

But, sadly, because their notion of life is so unique where they don’t look down upon commercial achievement and material progress, it gets seen as shallow. He asks with bewilderment – is it our fault if we are a prosperous community and like to enjoy life with the money we’ve earned through our hardwork? After all, everyone has the right to sustenance, don’t they?

To Harvinder, it’s not the Punjabi idea of life that needs refinement, it is the beholder’s eyes. Because refinement is ingrained in every aspect of a Punjabi life. According to Harvinder, Punjabis love taking on challenges because they’re a race that had to earn its right to survive. Hence, taking on challenges is a sign of respectability in Punjab. And bravery is a virtue of nobility.

But what was refreshing was how Harvinder defined bravery. Bravery, for him and Punjabis in general, is not about violence but taking on each day. He said profoundly, “Bravery is not about physically fighting with people. That’s reducing such a great virtue to one kind of behaviour. Courage is far bigger than just that. Courage is the way you tackle life’s challenges daily.”

For Harvinder, going to work everyday in the hope that there will be enough business, negotiating uncertainty and obstacles in order to earn a living so he can sustain his family is a kind of battle in itself. And facing such uncertainty with confidence, sharp decision-making and adaptability to each situation on a daily basis is bravery.

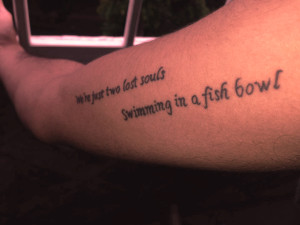

And this manifestation of courage leads to an even bigger and purer concept of refinement for Punjabis, something that had a lasting and mind-opening impression on us. For Harvinder, the pursuit of salvation or moksha is not exclusive of the daily life. In fact, that is what we heard from other Punjabis too. Salvation is not some other-worldly experience that one needs to attain by deserting one’s loved ones and spending time away in a forest waiting for enlightenment. Contemplation must come from the everyday, by immersing oneself in the everyday. Each day for Harvinder is pure and noble. And working hard everyday being satisfied with whatever one achieves is a virtue of the good and the noble.

True salvation for Punjabis is not in seclusion but in inclusion, not in shunning but taking responsibility. Supporting one’s family, taking responsibility for their well-being and striving for happiness is an evolved virtue and the trait of a refined person. Salvation, as Harvinder puts it, is not an individual concept. “My family is a part of me. If my salvation doesn’t include them, it’s not salvation. It’s further entrapment.”