Over the last several decades, India’s present has been written in a language that isn’t one of its own but one that the country has prided itself on as if it were its own progeny – English.

Since the turn of the millennium, the English language has slowly been making inroads into smaller towns and villages of India. Influenced by factors like the spread of English-medium schools, the explosion of English language TV channels and the internet, many people here have not only adapted but have also embraced the new language.

However, how has small town India actually adopted, absorbed and adapted to English? Is the language a handbook to the outside world? Is it a business opportunity? Is it a status symbol or a sign of progress? How has access to the online world influenced the role of English for young people in small town India?

Armed with these questions and a camera, we set out to immerse ourselves in Itarsi and Harda – tier-three towns in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh (India’s largest state by area yet one of its less-developed ones) to discover the welcome English has been given in small-town India.

The Business of English

Deepak Dugya, 37, runs a company called Noble Computers that offers a specialized course in English training called Smartalk. He set up the franchise two years ago to tap into Itarsi’s growing appetite for the language. The course typically spans four months and uses standardized modules developed by the franchise owners. Classes are delivered through interactive computer software’s and regular classroom sessions.

Smartalk, he says, is a ‘brand’ in this category and explains it’s pricing of Rs.4000, almost double the cost of other courses in the city. We stress on both grammar and pronunciation, while the other courses focus only on spoken English. Deepak himself doesn’t teach, although his two degrees, including a master’s in English literature, would probably qualify him for the job.

The venture however, is not performing as expected. Students are hesitant to spend, he says, preferring to go for cheaper courses that are not only easier but also shorter in duration. The city’s environment too doesn’t offer many occasions to practice the language and most students leave after a few months of training. This has meant charging a monthly fee over a lump sum upfront. Even targeted Facebook ads and print advertising have failed to pull in the crowds. The latest buzz was around a competitor offering a English course for a mere Rs.150.

Undeterred, Deepak has now launched Bachpan, a playschool franchise in the same building. The course curriculum is entirely in English while the teachers use a combination of Hindi and English to train the toddlers. Such systems, he hopes, will help bring about change from the roots. Children are more willing to learn compared to adults, and parents are more willing to spend on quality English education. He’s optimistic having seen a healthy enrolment of 75 students in the first year.

Bachpan currently operates till class KG, but Deepak hopes to expand it till class 5 in the coming year. This would mean expansion into another facility or using the floor currently occupied by the struggling Smartalk.

Puneet Soni went to a Hindi medium school in Itarsi before moving to Bhopal to study pharmacy. His Hindi background might have been a big problem in college if he hadn’t taken English classes from Mrs. Kothari, Itarsi’s best English teacher. So, he began doing well in Bhopal.

During his first year there, he noticed a demand for good internet cafes, being a regular at them himself. Sensing a business opportunity, he decided to move back home to Itarsi before his first year of college was up to open up an internet cafe of his own in the heart of Itarsi’s market area.

Apart from the usual suspects (school and college kids), his customers include medical representatives and local businessmen. The medical reps use the computers to keep in touch with their regional office – often in Bhopal – and to follow up on sales orders; a lot of this official work is done in English. Businessmen come there to view and print orders from different parts of the country. With India having 22 official languages and several more languages and dialects, English is often the language best understood by both customers and the businessmen. A lot of their work is conducted in Hindi too, especially if the customers are located in the same region. One other group of people who frequent the cafe are investors, who come there to follow the stock market and catch up on the latest financial news – most of which is in English. They often don’t invest online, though, preferring to walk to the investment services franchisee store around the corner instead.

The Language of Remedy

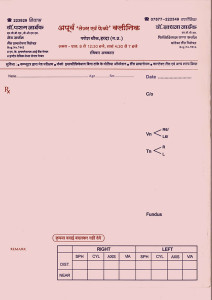

Doctor Parag Nayak is one of the leading ophthalmologists in the Harda district, about 3 hours away from Itarsi. His clinic – The Apoorv Eye Clinic offers state of the art services like laser surgery and has a large pharmacy attached to it. On a typical day, he sees close to 40 patients, many of whom come from nearby villages and surrounding towns.

Communication often becomes a problem in these situations. Most of these patients are familiar with Hindi while most prescriptions are written in English. This often leads to a situation where the patient is unclear about his medicines, but trusts the doctor purely on the basis of their relationship.

The use of English, Dr. Nayak says, is a necessary evil when it comes to medicine. Most procedures have very specific names and translating them into Hindi is not just difficult but sometimes impossible. A recent patient of his for example had to undergo a surgery for the removal of an entire eye socket. The correct medical terminology for this procedure is the ‘exculpation of the cornea’, which would be impossible to translate into Hindi. To ease the patient, he sometimes chooses to explain the problem in simpler Hindi analogies. In this case for example, he would describe the procedure as ‘galna’ or melting the waste components of the eye.

Prescribing in English has another key purpose. It is the only language that is understood by doctors across the country. The entire medical fraternity studies medicine entirely in English and this way all prescriptions can be read and understood by any doctor, irrespective of which part of the country he or she belongs too.

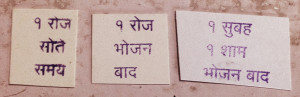

What about the patients then? How do they know what medicines to take and when to take them? This he says is where the local chemist comes in. Most chemists have a minimum of a B. Pharma degree, which ensures that they have a working knowledge of the English language. They read the prescriptions and attach a ‘Hindi tag’ detailing out the course of the medicines in Hindi. All the patient does then is follow the instructions, even if he can’t read the prescription himself.

For Gaurav Agarwal, putting up the sign “Your pharmacy family” (he called it their motto) above his medical store was a moment of pride when he returned to Itarsi to join the family business. The Agrawals opened a general store in 1946, a year before Independence. Some years ago, they decided to turn it into a pharmacy. That was the reason why Gaurav, after finishing school in Itarsi, decided to get an MPharm degree from Indore.

Unlike his three older sisters, Gaurav went to an English medium school. That really came in handy when he started college because Hindi medium students, the majority of the student body, really struggled because the pharmacy courses were always in English. Medical science needs a lingua franca and English is the preferred language worldwide. As a result, medical colleges are English only and doctors’ prescriptions are always in English. So the people interpreting the prescriptions and explaining them to patients who often don’t understand the language – pharmacists – need to be fluent in English. Gaurav says many students struggle for a year or even two, having trouble with classes and presentations. But, by studying extra on their own or by taking English lessons, they catch up and learn the language.

Gaurav is proud to be one of the only masters degree holders in town and he puts his education to use as much as possible, even when it comes to the little things. Like the green cross on the Madan Chemist sign. He explains that the green cross is the international symbol for pharmacists, not the red one commonly seen outside pharmacies. That’s only for Red Cross, he says. But customers just don’t know the difference. He’s mildly disappointed that, till date, no one in Itarsi has asked him about the motto or the green cross. He’s hopeful it’ll happen someday, though.

The Portal to English

Jeetu, 28, works at the New Agrawal Mobile shop, a mobile repair and accessory shop in the main market of Itarsi. He has recently joined his father full time at the shop, after trying his hand at a few other jobs post graduation. Most business families prefer their children to work with them, he says. Only the service class allow their children to work in other cities like Bhopal and Indore. He himself was interested in an MBA from Bhopal but wasn’t allowed to pursue it. Today many of his school friends work in different cities across the country. Some have even gone abroad successfully.

People here can’t speak English, he says, but they can understand some words if they are written in Hindi. He points at the words ‘Downloading’ displayed prominently on a standee outside his shop. So this is also an internet café? No, downloading into the phone he explains. The shop offers a service that downloads movies and songs from the internet and then loads (downloads) them into the memory card of the users phone. This is meant for locals who are not familiar with the internet. The typical rate for 2GB of content is 50Rs.

Shops like Jeetu’s get their content from registered distributors like Star Copyright Protection, a content owner that sells 1000GB of data at Rs.8000 a year and also issues a No Objection certificate to ward off police raids. Most of the demand is around the latest Hindi movies and music. Action films like Harry Potter and Transformers are also popular. Foreign films, he says with a wink, are quite high on demand too.

Every evening, Puneet, who owns his own internet café, hangs out at the cafe with his younger brother and a gang of friends. It’s their daily hour or two of goofing off – fooling around, checking out the latest jokes shared on Whatsapp and making friends with girls on Facebook. They aren’t 100% fluent in English, but they might use it to impress girls over the first few messages; eventually, things switch to Hindi. If they aren’t sure how to say what they want to in English, they turn to a trusty friend – Google Translate. This comes in handy when they’re speaking with girls from a little outside Itarsi – like Japan or the Philippines. When they hear back in, say, Japanese, it’s back to Google Translate to figure the Hindi equivalent. With local girls, they’ll often communicate online in Hindi but type things out phonetically in the English alphabet.

English Only Behind Closed Doors

Up a narrow flight of stairs, just above her husband’s plywood shop, is the home and classroom of Mrs. Kothari or Kothari Ma’am – a prominent English teacher in the city for the last 14 years. My students speak English fluently, she boasts, sometimes even better than those from the metros. And they come from all backgrounds too – rich, poor, students, mothers, parents, businessman, even the elderly.

There is a huge demand for English here, she says, but most people are afraid of the language. They see it as something alien and hesitate to speak it when there are people around. This discourages them immensely. Most shift back to Hindi the moment they step out of class.

Her solution to this conundrum seems almost counterintuitive. Parents, she says, shouldn’t send their children to English medium schools until they can speak English as fluently as they speak Hindi at home. Language should never become a hurdle to acquiring knowledge. Until such time, a rich Hindi medium education will prove far more beneficial for a student’s future.

And yes, please let them SMS and use their phones! These help in practicing the English language. Maybe this way, the condition will be better in the next 10 to 12 years.

For the Bajpai family – Mukund, a general manager at the local Campa Cola factory, his wife Chitra, their three children Sarvesh, Aprajita & Ajita and Chitra’s father, Nileshji, a retired chartered accountant, English finds it’s comforts in varied ways.

Most of Mukund’s work involves dealing with bottlers and distributors, and Hindi is the chosen medium of communication. Everyone speaks Hindi at work, he says. We use English only when it comes to financial matters like accounting, tax forms, stocks statements and sometimes while dealing with the sales team. Hindi is essentially the business language around here.

Mukund himself studied at a Hindi medium, and learnt English on the job. He say’s the environment in the city does not encourage the use of the language. Those who do know hesitate to speak it in fear of making a mistake.

These adults are now trying to counter their awkwardness with the language. Tata Sky English for example has become a convenient way to learn the language at a nominal cost. English commentary too was an important way to hear and practice English till recently. A recent shift to Hindi programming, say NileshJi, has removed this option altogether.

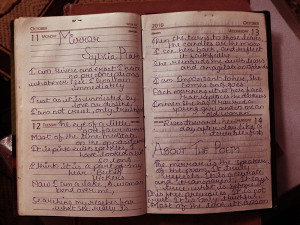

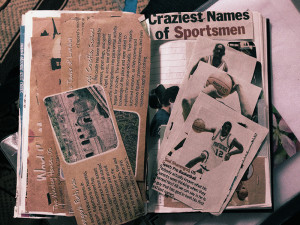

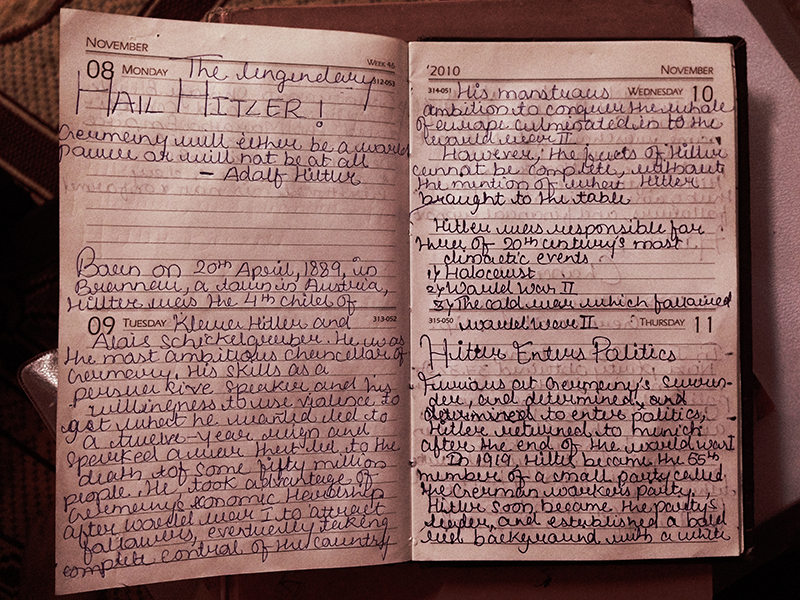

An anomaly to this is 17 year old Akriti Jaiswal or Bulbul, Mrs. Jaiswal’s niece who also lives next door. Akriti has taken to English like a fish to water. So much so that she passes in English easily, but struggles to clear her Hindi papers. English is more easier to write, she says, and explains how she often translates her Hindi class lectures into shorthand English notes. Her other passion is writing – an interest she enjoys through a regular journal capturing events, stories and poems that she find’s interesting. The topics vary across Diwali essays, poetry by Sylvia Plath, news about basketball stars and Hitler. Political figures, she tells us coyly, are her favourite and she’s read quite a few biographies by famous leaders, including one by the Führer.

The Enabler

Sister Clara arrived in Itarsi many years ago, determined to help the area’s children. At Itarsi’s railway station, a major junction in the Indian Railways’ vast network, she noticed several children spending their days by the tracks, trying to earn a livelihood. Many of them had no families or homes to turn to, leaving them extremely vulnerable.

Sister Clara began by sitting with them on the platforms, teaching them English poems and rhymes, and getting the children to sing them together. Soon, she managed to convince the railway authorities to let her use a spare room in the station as a makeshift shelter for the children.

A chance encounter with a traveling couple from the UK, the Butterfields, was the next major turning point. The Butterfields, already in love with India, were blown away by Sister Clara’s story. They decided to help her however they could. To figure out how, the Butterfields and the Sister Clara asked the children what they would like to have. The answer was simple – a home. So, with the Butterfields’ help, a plot of land was bought, a home was built and Sister Clara’s charitable organization got a name – Jeevoday.

Since then, Sister Clara has expanded her goals – she’d like all her kids to get a solid education and go on to lead happy lives. Understanding the need to know how to communicate well in English, she tries her best to teach them English in any way possible. Some of her ideas have involved using the services of the local priest, Father Rohan and a retired Navy colonel to take English lessons during the summer. As an incentive, she even promised to reward the children who scored above 85% in their exams by transferring them to an English medium school.

This last idea, though, got a little resistance from the Butterfields. They believed that Indians should learn their own language well and didn’t really need to focus on English that much. So Sister Clara eventually couldn’t fulfill that promise to the kids who did get 85% or more.

But she did manage to convince the Butterfields to help her send one of her boys, Ashok, to an English medium college in Bhopal to study commerce and computer science. Now, unbeknownst to them, Ashok is a pro – he speaks English fluently. He worked hard in Bhopal and made sure he kept improving. All the other kids at Jeevodaya now have an amazing role model to look up to. It’s pretty clear – everyone wants to be the next Ashok.

The Butterfields plan to visit Itarsi in December. Sister Clara plans to spring a fluently English-speaking Ashok on them to prove what she believed all along. She smiles at the thought. She can’t wait.